The last few posts have looked at expressing an odd prime p as a sum of two squares. This is possible if and only if p is of the form 4k + 1. I illustrated an algorithm for finding the squares with p = 2255 − 19, a prime that is used in cryptography. It is being used in bringing this page to you if the TLS connection between my server and your browser is uses Curve25519 or Ed25519.

World records

I thought about illustrating the algorithm with a larger prime too, such as a world record. But then I realized all the latest record primes have been of the form 4k + 3 and so cannot be written as a sum of squares. Why is p mod 4 equal to 3 for all the records? Are more primes congruent to 3 than to 1 mod 4? The answer to that question is subtle; more on that shortly.

More record primes are congruent to 3 mod 4 because Mersenne primes are easier to find, and that’s because there’s an algorithm, the Lucas-Lehmer test, that can test whether a Mersenne number is prime more efficiently than testing general numbers. Lucas developed his test in 1878 and Lehmer refined it in 1930.

Since the time Lucas first developed his test, the largest known prime has always been a Mersenne prime, with exceptions in 1951 and in 1989.

Chebyshev bias

So, are more primes congruent to 3 mod 4 than are congruent to 1 mod 4?

Define the function f(n) to be the ratio of the number of primes in each residue class.

f(n) = (# primes p < n with p = 3 mod 4) / (# primes p < n with p = 1 mod 4)

As n goes to infinity, the function f(n) converges to 1. So in that sense the number of primes in each category are equal.

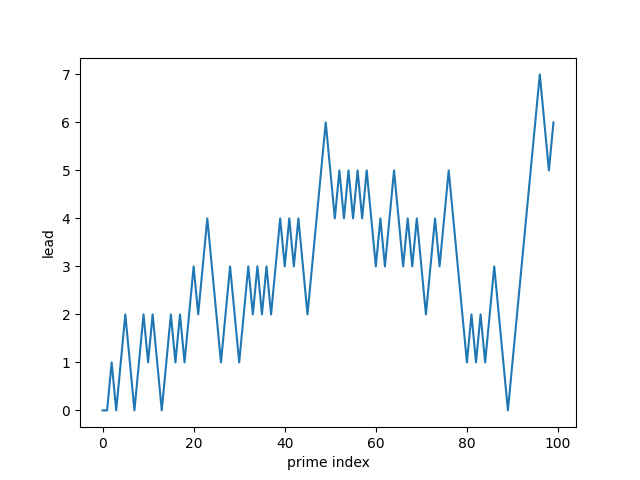

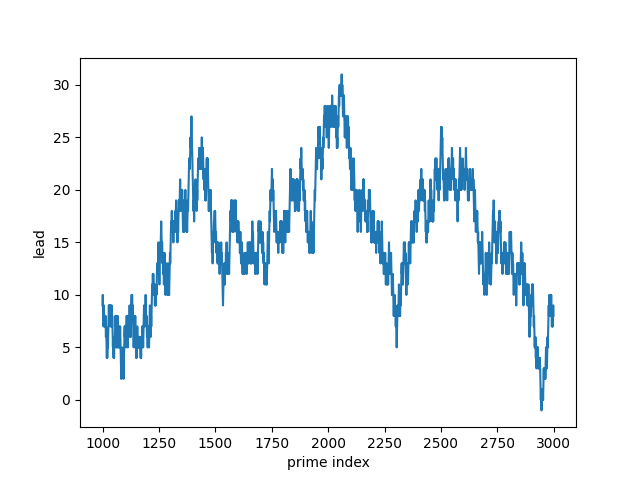

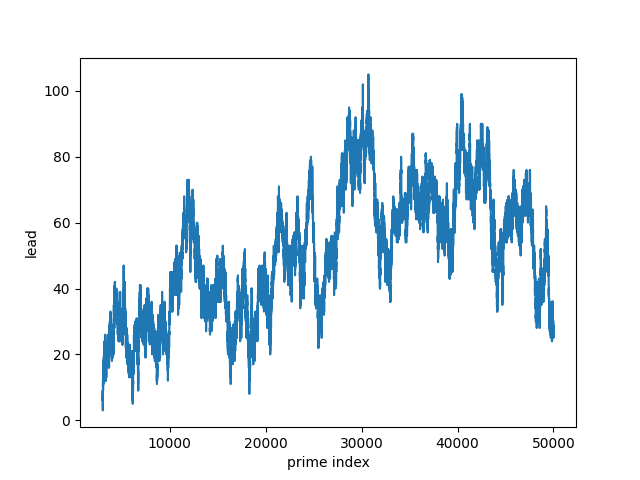

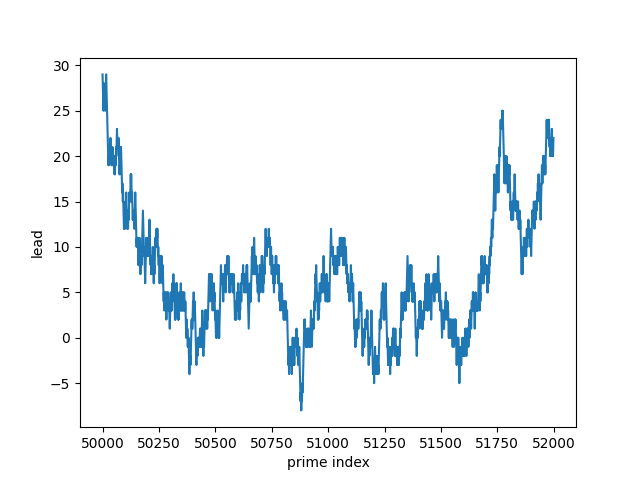

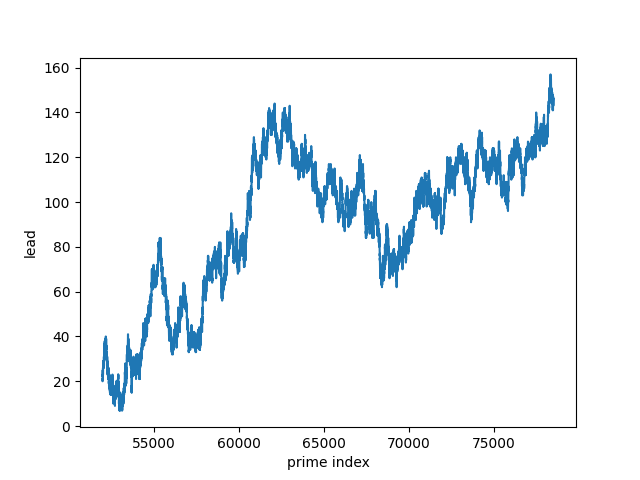

If we look at the difference rather than the ratio we get a more subtle story. Define the lead function to be how much the count of primes equal to 3 mod 4 leads the number of primes equal to 1 mod 4.

g(n) = (# primes p < n with p = 3 mod 4) − (# primes p < n with p = 1 mod 4)

For any n, f(n) > 1 if and only if g(n) > 0. However, as n goes to infinity the function g(n) does not converge. It oscillates between positive and negative infinitely often. But g(n) is positive for long stretches. This phenomena is known as Chebyshev bias.

Visualizing the lead function

We can calculate the lead function at primes with the following code.

from numpy import zeros

from sympy import primepi, primerange

N = 1_000_000

leads = zeros(primepi(N) + 1)

for index, prime in enumerate(primerange(2, N), start=1):

leads[index] = leads[index - 1] + prime % 4 - 2

Here is a list of the primes at which the lead function is zero, i.e. when it changes sign.

[ 0, 1, 3, 7, 13, 89, 2943, 2945, 2947, 2949, 2951, 2953, 50371, 50375, 50377, 50379, 50381, 50393, 50413, 50423, 50425, 50427, 50429, 50431, 50433, 50435, 50437, 50439, 50445, 50449, 50451, 50503, 50507, 50515, 50517, 50821, 50843, 50853, 50855, 50857, 50859, 50861, 50865, 50893, 50899, 50901, 50903, 50905, 50907, 50909, 50911, 50913, 50915, 50917, 50919, 50921, 50927, 50929, 51119, 51121, 51123, 51127, 51151, 51155, 51157, 51159, 51161, 51163, 51177, 51185, 51187, 51189, 51195, 51227, 51261, 51263, 51285, 51287, 51289, 51291, 51293, 51297, 51299, 51319, 51321, 51389, 51391, 51395, 51397, 51505, 51535, 51537, 51543, 51547, 51551, 51553, 51557, 51559, 51567, 51573, 51575, 51577, 51595, 51599, 51607, 51609, 51611, 51615, 51617, 51619, 51621, 51623, 51627]

This is OEIS sequence A038691.

Because the lead function changes more often in some regions than others, it’s best to plot the function over multiple ranges.

The lead function is more often positive than negative. And yet it is zero infinitely often. So while the count of primes with remainder 3 mod 4 is usually ahead, the counts equal out infinitely often.