Explosive datacenter demand has caused developers to leave no stone unturned in search of higher efficiencies. The DeepSeek team, not satisfied with Nvidia’s CUDA libraries, used a virtualized form of assembly language (PTX) to write kernel codes to accelerate their AI computations. Others have attempted to generate optimized kernels using AI, though some results have been questioned (for various attempts, see also here, here, here, here and here).

Why is it hard to write peak-speed GPU code? Writing really fast code has always been arduous, but it seems especially so for modern GPUs.

To understand the issues, my colleagues and I performed a detailed study of GPU kernel performance, across eight different GPU models from three GPU vendors [1]. The test case we considered was low precision matrix multiply, a resource-intensive operation for LLM training. We ran many, many experiments to understand what causes performance variability and why kernels sometimes run slower than you’d think they should.

For the cases we studied, we found about half a dozen different factors, but the upshot is this: modern processors like GPUs have become so complex—notably their multi-layered hierarchical memory subsystems—that it is difficult to get consistently high performance across all problem sizes a user might want to run in practice. As a result, the performance for the target problem might be surprisingly and mysteriously less than the advertised peak performance for the operation in question. The reasons might be obvious—like cache line misalignment—or more opaque. For the matrix multiply case, various issues like the need for prefetching, caching, tiling and block size selection, make it difficult for the kernel developer to optimize for every input size a user might specify.

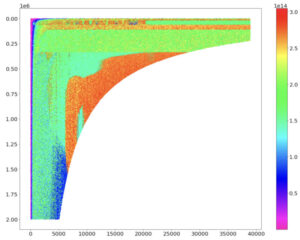

Below is an example graphic from our paper. The color indicates floating point operation rate (FLOPs) for a reduced precision matrix multiply on a representative GPU using a library call. The horizontal and vertical axes refer to the matrix dimensions for the problem (see paper for details). Though some regions show performance near the theoretical peak (red), other immediately adjacent regions show problem sizes that run dramatically less—in fact, only about half of peak performance, or less. Presumably this is because either individual kernel performance or the selection of kernels used by the library is suboptimal. The net outcome is, if your problem lands a “bad” region, you’re in for a big surprise, your performance will be much less than expected, and you may not understand why. All high-performing GPUs we tested showed irregular behaviors such as this [2] [3].

In the past this was not always a problem. Older architectures like Sun Sparc or Cray vector processor, complex as they were, were simple enough that a reasonably well-tuned computational kernel might run well across most if not all inputs [4]. Today, performance is much harder to predict and can vary substantially based on the requested problem sizes.

This is a tough challenge for library developers. Whenever a new GPU model family comes out, new kernel optimization and tuning are required to give (hopefully) more consistently high performance, and some cases get more developer attention than others due to customer needs and limited developer resources. As a result, infrequently used operations do not get as much attention, but they may be the exact ones you need for your particular case [5].

Tools are available to help optimize for specific cases. The excellent Nvidia CUTLASS library exposes access to many more fine-grained options compared to the standard cuBLAS library. The not faint of heart can try programming Nvidia GPUs at the level of PTX, or (shudder) SASS. Superoptimization might help, but only for very small code fragments and even then there may be too many external factors influencing performance to make it effective.

Autotuning is a promising approach though it doesn’t seem to have reached its full potential in production. AI might really help here [6]; in our own paper we had some success using machine learning methods like decision trees and random forests to model performance as a function of problem size, though our work was exploratory and not production-ready. To make a well-crafted general solution it would seem would require a lot of effort to do right. Code sustainability and maintenance are also critical; a sustainable workflow would be needed to retrain on new GPUs, new CUDA releases and even site-specific and system-specific settings like GPU power and frequency cap policies.

Most recent AI-driven work focuses on optimizing performance for one or a few problem sizes only. A truly production-quality general purpose tool would give both 100% accurate results and also top achievable performance for any input problem size (even for corner cases) or data type. This would require both optimized GPU kernels and optimal kernel dispatcher for kernel selection. And the method would need to be robust to issues like power and frequency variabilities in production runs. This would seem to currently be an unsolved problem. Solving it would be of huge benefit to the hyperscaler community.

Notes

[1] For related work from a slightly different angle, see this excellent work from Matt Sinclair’s lab.

[2] It turned out this study was helpful to us for production runs, to help us to triage an odd performance conundrum we encountered when attempting an exascale run (see here, here).

[3] Incidentally this example shows the hazards of simplistic benchmark suites to measure GPU code performance. Unless the benchmark captures a truly large and varied set of input cases, any new optimization method proposed can artificially “overfit” performance on the tests and still underperform miserably on many user cases of interest.

[4] I once wrote a 1-D wavelet convolution kernel for a Sparc processor, using a circular register buffer and loop unrolling to minimize loads and stores, this achieving near-peak performance. The code was correctly compiled from C to assembly, and performance for a given problem was almost precisely predictable. That was before the days of complex memory hierarchies.

[5] One vendor I know of used to take customer requests for hand tuning expensive library calls and made them run fast at the specific customer problem sizes.

[6] LLM kernel generation seems like a natural fit, particularly since LLM-generated code quality has much improved in recent months. Kernel selection and parameter selection for block size, tiling etc. might be better solved by direct training of machine learning models, or methods like this. Comparative studies on this would be informative.