This weekend I ran across a blog post The Rodeo Clown Theory of Personal Development. The title comes from a hypothetical example of a goal you don’t know how to achieve: becoming a rodeo clown.

Let’s say you decide you want to be a rodeo clown. And let’s say you’re me and you have no idea how to be a rodeo clown. … Can you look at the possibilities currently available to you and imagine which of them might lead to an overall increase of rodeo clowndom in your life, even infinitesimally?

Each day you ask yourself what you can do that might lead you closer to your goal. This is a greedy algorithm: at each step you make as much progress toward your goal as you can. Greedy algorithms are not always optimal, but the premise above is that you have no idea what to do. In that case, doing whatever you can imagine that might bring you a little closer to your goal is a smart thing to do.

Crossing the continent

If you’re in Los Angeles and your goal is to get to New York, you could start by walking east. You might run into a brick wall and decide that you should not take your approach too literally. Maybe you decide to buy a ticket for a bus that’s traveling east, even if you have to walk west to the bus station. Maybe the bus takes you to Houston. This isn’t the most direct route, but it’s progress.

When you don’t know what else to do, a greedy approach, especially one tempered with common sense, could be a very sensible way to start. Maybe it’ll put you in a position to learn of a more efficient approach. In the scenario above, maybe some stranger sees you walk into a wall, asks you what you’re trying to do, and tells you where the bus station is.

Sorting algorithms

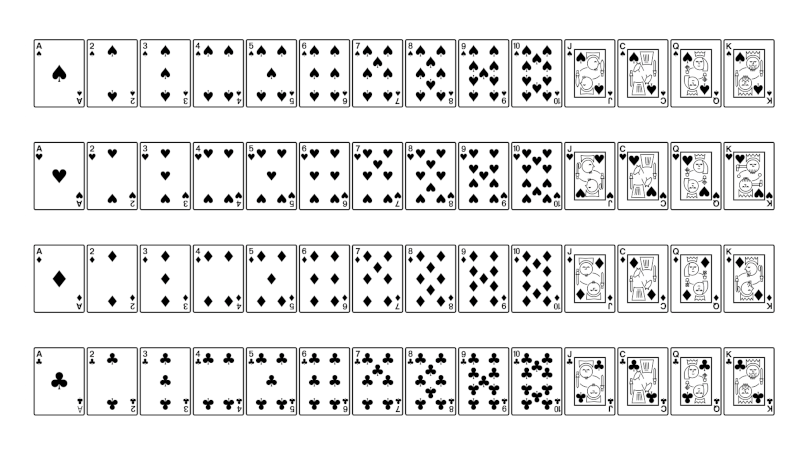

The way most people sort a hand of playing cards is a sort of greedy algorithm. They scan for the highest card and put it first. Then they scan the remainder of the hand for the next highest card and so on. This algorithm is known as insertion sort. It’s not the most efficient algorithm, but it may be the most natural, and it works. And for a hand of five cards it’s about as good as any.

Anyone who has taken an algorithms class will know you can beat insertion sort with a more sophisticated algorithm such as heap sort. But sorting is a well-understood, one-dimensional problem. That’s why people long ago came up with solutions that are better than a greedy approach. But when a problem is not well understood and is high-dimensional, greedy algorithms are more likely to succeed, even if they’re not optimal.

Training neural nets

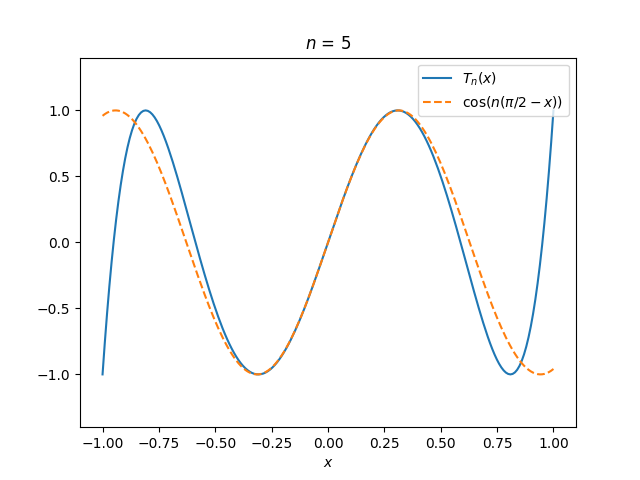

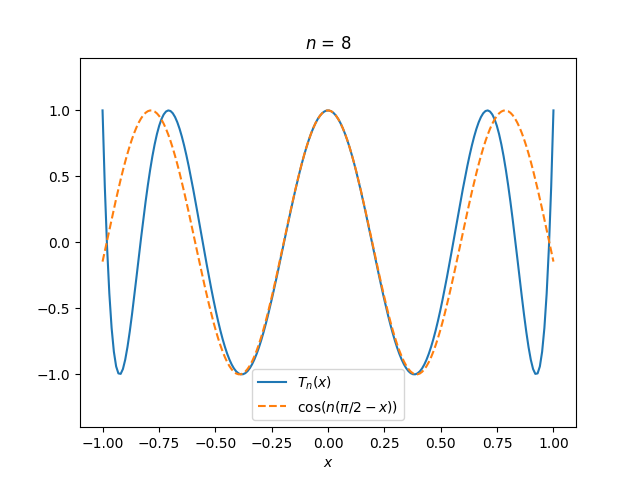

Training a neural network is a very high dimensional optimization problem, maybe on the order of a billion dimensions. And yet it is solved using stochastic gradient descent, which is essentially a greedy algorithm. At each iteration, you move in the direction that gives you the most improvement toward your goal. There’s a little more nuance to it than that, but that’s the basic idea.

How can gradient descent work so well in practice when in theory it could get stuck in a local minimum or a saddle point? John Carmack posted a heuristic explanation on Twitter a few weeks ago. A local critical point requires the “cooperation” of every variable in the function you’re optimizing. The more variables, the less likely this is to happen.

Carmack didn’t give a full explanation—he posted a tweet, not a journal article—but he does give an intuitive idea of what’s going on. At the global minimum, the variables cooperate for a good reason. He assumes the variables are unlikely to cooperate anywhere else, which is apparently often true when training neural nets.

Usually things get harder in higher dimensions, hence the “curse of dimensionality.” But there’s a sort of blessing of dimensionality here: you’re less likely to get stuck in a local minimum in higher dimensions.

Back to the rodeo

Training a neural network can be a huge undertaking, using millions of dollars worth of electricity, but it’s a mathematically defined problem. Life goals such as becoming a rodeo clown are not cleanly quantified problems. They are very high dimensional in the sense that there are a vast number of things you could do at any given time. You might argue by analogy with neural nets that the fact that there are so many dimensions means that you’re unlikely to get stuck in a local minimum. This is a loose analogy, one that easily breaks down, but still one worth thinking about.

Seth Godin once said “Remarkable work often comes from making choices when everyone else feels as though there is no choice.” What looks like a local minimum may be revealed to not be once you consider more options.

Image by Clarence Alford from Pixabay