If the earth were a perfect sphere, “down” would be the direction to the center of the earth, wherever you stand. But because our planet is a bit flattened at the poles, a line perpendicular to the surface and a line to the center of the earth are not the same. They’re nearly the same because the earth is nearly a sphere, but not exactly, unless you’re at the equator or at one of the poles. Sometimes the difference matters and sometimes it does not.

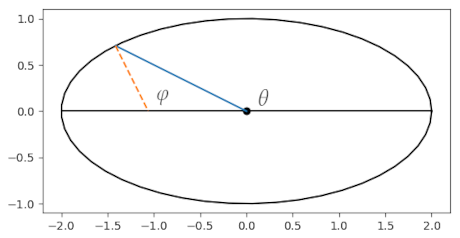

From a given point on the earth’s surface, draw two lines: one straight down (i.e. perpendicular to the surface) and one straight to the center of the earth. The angle φ that the former makes with the equatorial plane is geographic latitude. The angle θ that the latter makes with the equatorial plane is geocentric latitude.

For illustration we will draw an ellipse that is far more eccentric than a polar cross-section of the earth.

At first it may not be clear why geographic latitude is defined the way it is; geocentric latitude is conceptually simpler. But geographic latitude is easier to measure: a plumb bob will show you which direction is straight down.

There may be some slight variation between the direction of a plumb bob and a perpendicular to the earth’s surface due to variations in surface gravity. However, the deviations due to gravity are a couple orders of magnitude smaller than the differences between geographic and geocentric latitude.

Conversion formulas

The conversion between the two latitudes is as follows.

Here e is eccentricity. The equations above work for any ellipsoid, but for earth in particular e² = 0.00669438.

The function atan2(y, x) returns an angle in the same quadrant as the point (x, y) whose tangent is y/x. [1]

As a quick sanity check on the equations, note that when eccentricity e is zero, i.e. in the case of a circle, φ = θ. Also, if φ = 0 then θ = φ for all eccentricity values.

Next we give a proof of the equations above.

Proof

We can parameterize an ellipse with semi-major axis a and semi-minor axis b by

The slope at a point (x(t), y(t)) is the ratio

and so the slope of a line perpendicular to the tangent, i.e tan φ, is

Now

and so

where e² = 1 − b²/a² is the eccentricity of the ellipse. Therefore

and the equations at the top of the post follow.

Difference

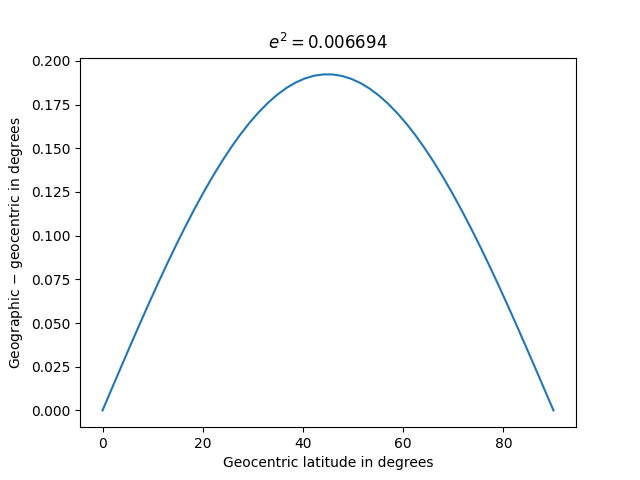

For the earth’s shape, e² = 0.006694 per WGS84. For small eccentricities, the difference between geographic and geocentric latitude is approximately symmetric around 45°.

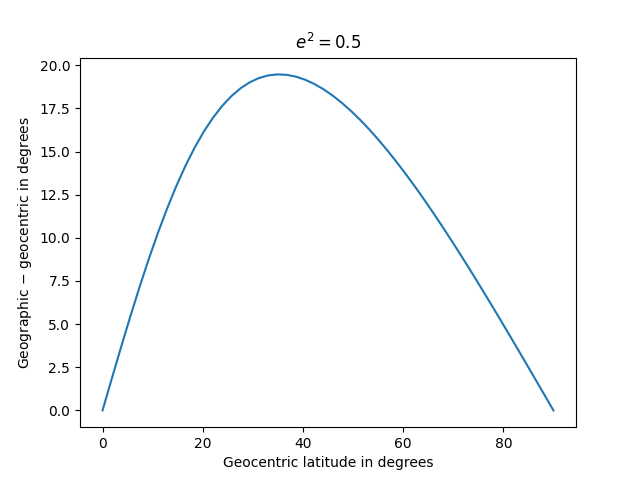

But for larger values of eccentricity the asymmetry becomes more pronounced.

Related posts

[1] There are a couple complications with programming language implementations of atan2. Some call the function arctan2 and some reverse the order of the arguments. More on that here.

But isn’t down the direction in which objects fall when released and thus the direction to the center of gravity of the earth? (:-))

expr’s comment led me to imagine a planet with a cross-section like that pictured, on which a ball released near the equator would roll with extreme but diminishing acceleration to a pole, and thereafter would act as a sort of pendulum. This seems to imply that such a configuration of matter would be quite unlikely, which it probably is…

How does a plumb bob manage to point “perpendicular to the local surface” rather than pointing in the direction of gravity?

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00190-015-0844-y

Why the Greenwich meridian moved.

“the authors show that the deflection of the vertical (DoV) can account for the entire longitude shift at Greenwich. “