Pairings can mean a variety of related things in group theory, but for our purposes a pairing is a bilinear mapping from two groups to a third group.

e: G1 × G2 → GT

Typically the group operation on G1 and G2 is written additively and the group operation on GT is written multiplicatively. In fact, GT will always be the multiplicative group of a finite field, i.e. GT consists of the non-zero elements of a finite field under multiplication. (The “T” stands for “target.”)

Here bilinear [1] means that if P is an element of G1 and Q is an element of G2, and a and b are nonnegative integers,

e(aP, bQ) = e(P, Q)ab.

There are a few provisos …

First, the pairing must be non-degenerate, i.e. e(P, Q) ≠ 1 for some P and Q.

Second, the pairing must be efficiently computable.

Third, the embedding degree must not be “too high.” This means that if GT is the multiplicative group of a field with pk elements, k is not too big. We will look at two examples in which k = 12.

The second and third provisos are important even though they’re not stated rigorously.

Cryptography often speaks of pairing elliptic curves, but in fact it uses pairings of prime-order subgroups of the additive groups of elliptic curves. Because the subgroups have prime order, they are cyclic, and so the pairing is determined by its value on a generator from each subgroup.

Example: BN254

The previous post briefly mentioned a pairing between two elliptic curves, BN254 and alt_bn128, that is used in Ethereum and was used in Zcash in the original Sprout shielded protocol.

The elliptic curve BN254 is defined over the field Fp, the integers mod p, where

p = 21888242871839275222246405745257275088696311157297823662689037894645226208583.

and the elliptic curve alt_bn128 is defined over the field Fp[i], i.e. the field Fp, with an imaginary element i adjoined.

Both elliptic curves have a subgroup of order

r = 21888242871839275222246405745257275088548364400416034343698204186575808495617,

which is prime. So in the pairing the groups G1 and G2 are isomorphic to the integers mod r. The target group GT has order p12 − 1 and so the embedding degree k equals 12, and so the embedding degree is “not too high.”

Example: BLS12-381

Another example also comes from Ethereum and Zcash. Ethereum uses BN254 in smart contracts, but it uses BLS12-381 in its consensus layer. Zcash switched from BN254 to BLS12-381 in the Sapling release.

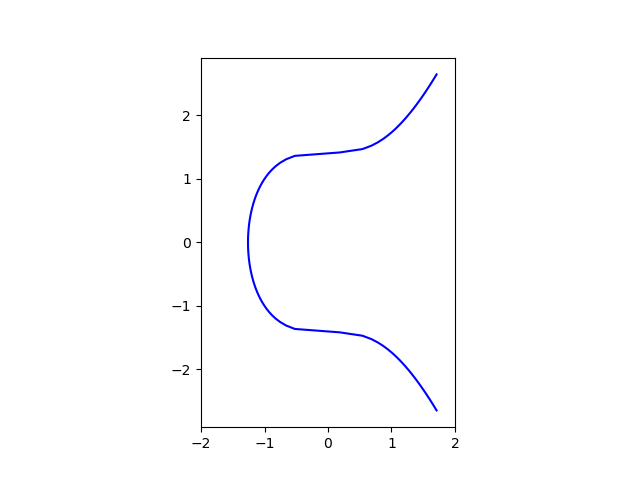

BLS12-381 is defined over a prime order field with on the order of 2381 elements and has embedding order 12, hence 12-381. The BLS stands for Paulo Barreto, Ben Lynn, and Michael Scott. Elliptic curve names often look mysterious, but they’re actually pretty descriptive. I discuss BLS12-381 in more detail here. As in the example above, BLS12-381 is defined over a field Fp and is paired with a curve over Fp[i], i.e. the same field with an imaginary element adjoined. The equation for BLS12-381 is

y² = x³ + 4

and the equation for the curve it is paired with is

y² = x³ + 4(1 + i)

As before the target group is the multiplicative group of a finite field of order p12.

Related posts

[1] You’ll also see bilinearity defined by

e(P + Q, R) = e(P, R) e(Q, R)

and

e(P, R + S) = e(P, R) e(P, S).

These definitions are equivalent. To see that the definition here implies the definition at the top, write out aP as P + P + … + P etc.

Since we’re working in subgroups of prime order, there is a generator for each subgroup. Write out each element as a multiple of a generator, then the definition at the top implies the definition here.