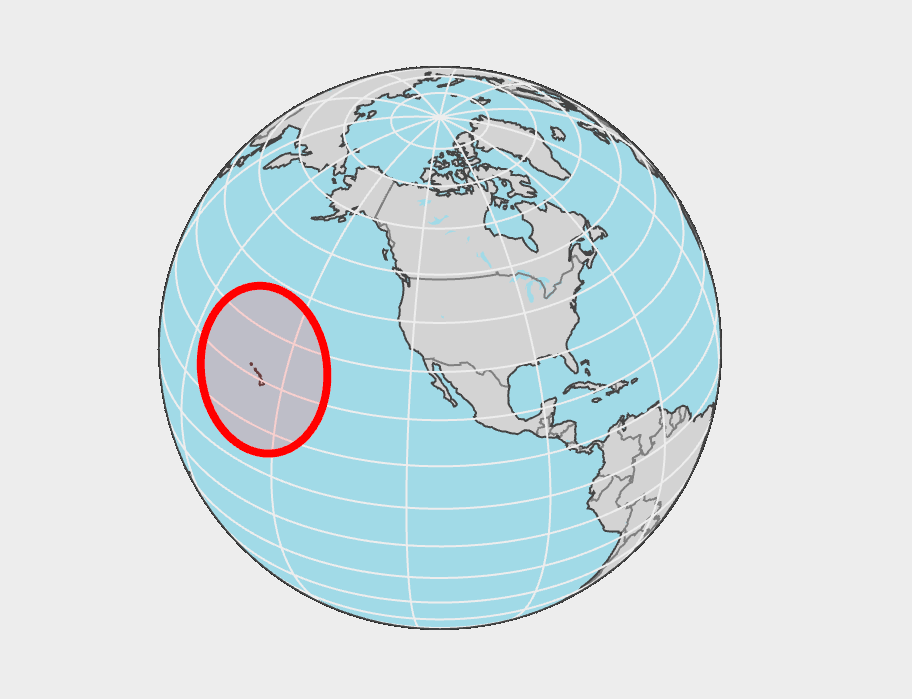

The previous post introduced the idea of finding your location by sighting a star. There is some point on Earth that is directly underneath the star at any point in time, and that location is called the star’s GP (geographic position). That is one vertex of the navigational triangle. The other two vertices are your position and the North Pole.

Unless you’re at Santa’s workshop and observing a star nearly directly overhead, the navigational triangle is a big triangle, so big that you need to use spherical geometry rather than plane geometry. We will assume the Earth is a sphere [1].

Let a be the side running from your position to the GP. In the terminology of the previous post a is the radius of the line of position (LOP).

Let b be the side running from the GP to the North Pole. This is the GP’s lo-latitude, the complement of latitude.

Let c be the side running from your location to the North Pole. This is your co-latitude.

Let A, B, and C be the angles opposite a, b, and c respectively. The angle A is known as the local hour angle (LHA) because it is proportional to the time difference between noon at your location and noon at the GP.

Given three items from the set {a, b, c, A, B, C} you can solve for the other three [2]. Note that one possibility is knowing the three angles. This is where spherical geometry differs from plane geometry: you can’t have spherical triangles that are similar but not congruent because the triangle excess determines the area.

If you know the current time, you can look up the GP coordinates in a table. The complement of the GP’s latitude is the side b.

Also from the current time you can determine your longitude, and from that you can find the LHA (angle A).

As described in the previous post, the altitude of the star, along with its GP, determines the LOP. From the LOP you can determine the arc between you and the GP, i.e. side a. We haven’t said how you could determine a, only that you could.

If you know two sides (in our case a and b) and the angle opposite one of the sides (in our case A) you can solve for the rest.

Adding detail

This post is more detailed than the previous, but still talks about what can be calculated but now how. We’re adding detail as the series progresses.

To motivate future posts, note that just because something can in theory be computed from an equation, that doesn’t mean it’s best to use that equation. Maybe the equation is sensitive to measurement error, or is numerically unstable, or is hard to calculate by hand.

Since we’re talking about navigating by the stars rather than GPS, we’re implicitly assuming that you’re using pencil and paper because for some reason you can’t use GPS.

Related posts

[1] To first approximation, the Earth is a sphere. To second approximation, it’s an oblate spheroid. If you want to get into even more detail, it’s not exactly an oblate spheroid. How much difference does all this make? See this post.

[2] In some cases there are two solutions for one of the missing elements and you’ll need to use additional information, such as your approximate location, to rule out one of the possibilities. More on when solutions are unique here.