From Paul Graham:

When you’re forced to be simple, you’re forced to face the real problem. When you can’t deliver ornament, you have to deliver substance.

From Paul Graham:

When you’re forced to be simple, you’re forced to face the real problem. When you can’t deliver ornament, you have to deliver substance.

Here’s a little advice to students picking electives.

Consider taking classes in those things that would be hardest to learn on your own after you graduate. Taking the most advanced courses available in your major may not be the best choice. Presumably you’ve learned how to learn more about your area of concentration. (If not, your education has failed you.) So the advanced courses might teach you the material you’re best prepared to learn on your own.

Maybe it would be better to take a foundational course in a related area than an advanced course in your main area. For example, I suggested to some statistics graduate students yesterday that they take a really good linear algebra class rather than taking all the statistics they can. If they become professional statisticians, they’ll continue to learn statistics (I hope!) but they may find it harder to take the time to really understand mathematical foundations.

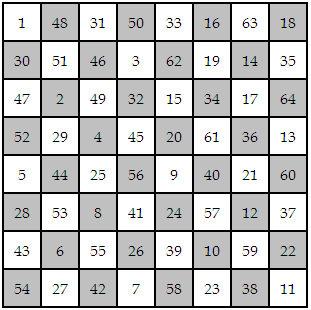

This magic square was created by Leonhard Euler (1707-1783). Each row and each column sum to 260. Each half-row and half-column sum to 130. The square is also a knight’s tour: a knight could visit each square on a chessboard exactly once by following the numbers in sequence.

Here is Python code to verify that the square has the properties listed above.

Update: It seems the attribution to Euler is a persistent error. Euler did publish the first paper on knight’s tours, but the knight’s tour square above was published by William Beverley in 1848. Thanks to George Jelliss for the correction. See the comments below.

Update 2: Notes from George Jelliss on magic king and queen tours.

Update 3: This is technically a semi-magic square: the rows add up to the same magic constant, but the diagonals do not. See Magic square errata.

Here’s an interesting account of the largest known primes over time. Thanks to @mathematicsprof for pointing this out.

Ever since 1952, the largest known prime has been a Mersenne prime, with one exception in 1989. One reason is that it is simple to test whether Mersenne numbers are prime using the Lucas-Lehmer test. The algorithm is described in seven lines of pseudo-code here.

Here are a couple connections with Mersenne and his primes I’ve written about before. First, Mersenne is one of my mathematical ancestors. Second, Mersenne primes are intimately connected with even perfect numbers, a connection that has been known since Euclid.

Software generally gets better over time, but this does not mean it’s getting better and better every day in every way.

Software quality has so many dimensions that it is impossible to make progress along every front with every release of every product. Life’s full of trade-offs. A successful software project will improve over time in the ways that matter to most of its constituents. That doesn’t mean that every user will be better served by each subsequent release, especially if the user base changes.

It’s inevitable that some software will get worse over time, as far as a minority of users is concerned. See, for example, this post about Word Perfect.

Commercial software may disappoint tech savvy users over time as such users make up a diminishing proportion of the software market. One reason programmers often prefer open source software is that they are the target market for the software.

The dynamics of open source software are more complex. Software written by volunteers is driven by what volunteers find interesting. This could result in software becoming wonkier over time, delighting geeks and alienating the general population. However, many volunteer developers find it interesting to make software easy to use for a wide audience.

And not all open source software is developed by volunteers. For example, the majority of work on the Linux kernel is done by corporate employees. The companies paying for the development have a commercial interest in the software, even though they don’t sell the software. Commercial and non-commercial are fuzzy concepts.

A company may sponsor an open source project because they rely on the software. Or maybe they want to undermine a competitor who sells an analogous project. Or maybe they’re sponsoring a project because they want to crow that they sponsor open source projects. Each of these motivations could make a project better for a different constituency.

Related post: Software development and the myth of progress