Everybody cares about codes running fast on their computers. Hardware improvements over recent decades have made this possible. But how well are we taking advantage of hardware speedups?

Consider these two C++ code examples. Assume here n = 10000000.

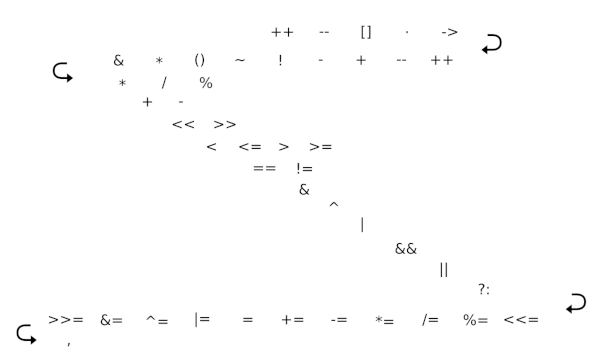

void sub(int* a, int* b) {

for (int i=0; i<n; ++i)

a[i] = i + 1;

for (int i=0; i<n; ++i)

b[i] = a[i];

}

void sub(int* a, int* b) {

for (int i=0; i<n; ++i) {

const int j = i + 1;

a[i] = j;

b[i] = j;

}

}

Which runs faster? Both are simple and give identical results (assuming no aliasing). However on modern architectures, depending on the compilation setup, one will generally run significantly faster than the other.

In particular, Snippet 2 would be expected to run faster than Snippet 1. In Snippet 1, elements of the array “a”, which is too large to be cached, must be retrieved from memory after being written, but this is not required for Snippet 2. The trend for over two decades has been for compute speed of newly delivered systems to grow much faster than memory speed, and the disparity is extreme today. The performance of these kernels is bound almost entirely by memory bandwidth speed. Thus Snippet 2, a fused loop version of Snippet 1, improves speed by reducing main memory access.

Libraries like C++ STL are unlikely to help, since this operation is too specialized to expect a library to support it (especially the fused loop version). Also, the compiler cannot safely fuse the loops automatically without specific instructions that the pointers are unaliased, and even then is not guaranteed to do so.

Thankfully, high level computer languages since the 1950s have raised the programming abstraction level for all of us. Naturally, many of us would like to just implement the required business logic in our codes and let the compiler and the hardware do the rest. But sadly, one can’t always just throw the code on a computer and expect it to run fast. Increasingly, as hardware becomes more complex, giving attention to the underlying architecture is critical to getting high performance.