One of the more subtle ideas to convey in an introductory statistics class is that statistics have distributions.

Students implicitly think that when you calculate a statistic on a data set, say the mean, that then you have THE mean. But if your data are (modeled as) samples from a random variable, then anything you compute from those samples, such as the mean, is also a random variable. When you compute a useful statistic, it’s not as random as the data, i.e. it has smaller variance, but it’s still random.

A couple days ago I wrote about Fisher’s transform to make the distribution sample correlations closer to normal. This post will make that more concrete.

Preliminaries

We’ll need to bring in a few Python libraries. While we’re at it, let’s set the random number generator seed so the results will be reproducible.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import skew

np.random.seed(20251020)

Correlated RNG

Next, we’ll need a way to generate correlated random samples, specifying the correlation ρ and the sample size N.

def gen_correlated_samples(rho, N):

mean = [0, 0]

cov = [

[1, rho],

[rho, 1]

]

return np.random.multivariate_normal(mean, cov, size=N)

Calculating correlation

Once we generate correlated pairs, we need to calculate their correlation. To be more precise, their linear (Pearson) correlation. To do this we’ll find the empirical covariance matrix, the sample counterpart to the covariance matrix specified in the generator code above. The correlation coefficient is then the off-diagonal element of the covariance matrix.

def pearsonr(X):

correlation_matrix = np.corrcoef(X[:,0], X[:,1])

return correlation_matrix[0, 1]

Simulation

Now we’re ready to do our simulation.

M = 10000

rs = np.zeros(M)

for i in range(M):

X = gen_correlated_samples(0.9, 100)

rs[i] = pearsonr(X)

Notice that there are two levels of sampling. We’re generating random samples of size 100 and computing their correlation; that’s sampling our underlying data. And we’re repeating the process of computing the correlation 10,000 times; that’s sampling the correlation.

Untransformed distribution

Next we view the distribution of the correlation values.

plt.hist(rs, bins=int(np.sqrt(M)))

plt.show()

plt.close()

This gives the following plot.

It’s strongly skewed to the left, which we can quantify by calculating the skewness.

print(skew(rs))

This tells us the skewness is −0.616. A normal distribution has skewness 0. The negative sign tells us the direction of the skew.

Transformed distribution

Now let’s apply the Fisher transformation and see how it makes the distribution much closer to normal.

xformed = np.arctanh(rs)

plt.hist(xformed, bins=int(np.sqrt(M)))

plt.show()

plt.close()

print(skew(xformed))

This produces the plot below and prints a skewness value of −0.0415.

Small correlation example

We said before that when the correlation ρ is near zero, the Fisher transformation is less necessary. Here’s an example where ρ = 0.1. It’s not visibly different from a normal distribution, and the skewness is −0.1044.

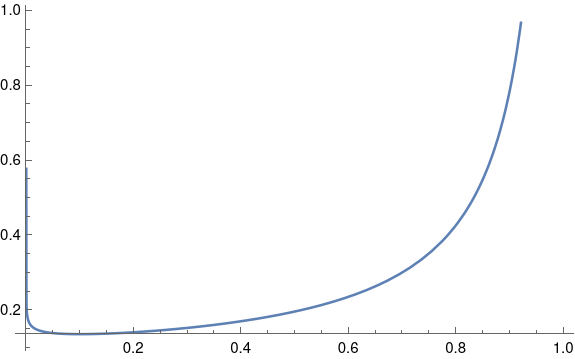

Observation and conjecture

In our two examples, the skewness was approximately −ρ. Was that a coincidence, or does that hold more generally? We can test this with the following code.

def skewness(rho):

rs = np.zeros(M)

for i in range(M):

X = gen_correlated_samples(rho, 100)

rs[i] = pearsonr(X)

return skew(rs)

rhos = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

ks = [skewness(rho) for rho in rhos]

plt.plot(rhos, ks)

plt.plot(rhos, -rhos, "--", color="gray")

plt.show()

Here’s the resulting plot.

It looks like the skewness is not exactly −ρ, but −cρ for some c < 1. Maybe c depends on the inner sample size, in our case 100. But it sure looks like skewness is at least approximately proportional to ρ. Maybe this is a well-known result, but I haven’t seen it before.