The following problem illustrates how the smallest changes to a problem can have large consequences. As explained at the end of the post, this problem is a little artificial, but it illustrates difficulties that come up in realistic problems.

Suppose you have a simple differential equation,

where y(t) gives displacement in meters at a time measured in seconds. Assume initial conditions y(0) = 1 and y'(0) = -1.

Then the unique solution is y(t) = exp(-t). The solution is decreasing and positive. But a numerical solution to the equation might turn around and start increasing, or it might go negative.

Suppose the initial conditions are y(0) = 1 as before but now y'(0) = -1 ± ε. You could think of the ε as a tiny measurement error in the initial velocity, or a limitation in representing the initial velocity as a number in a computer.

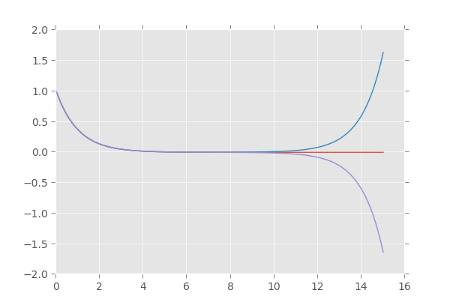

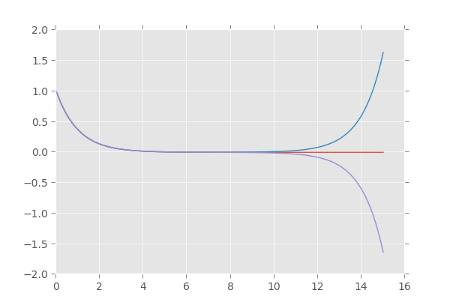

The following graph shows the solutions corresponding to ε = 10-6, 0, and -10-6.

The exact solution is

If the initial velocity is exactly -1, then ε = 0 and we only have the solution exp(-t). But if the initial velocity is a little more than -1, there is an exponentially increasing component of the solution that will eventually overtake the exponentially decreasing component. And if the initial velocity is a little less than -1, there is a negative component increasing exponentially in magnitude. Eventually it will overtake the positive component and cause the solution to become negative.

The solution starts to misbehave (i.e. change direction or go negative) at

If ε is small, 2/ε is much larger than 1, and so the final 1 above makes little difference. So we could say the solution goes bad at approximately

whether the error is positive or negative. If ε is ±0.000001, for example, the solution goes bad around t = 7.25 seconds. (The term we dropped only effects the 6th decimal place.)

On a small time scale, less than 7.25 seconds, we would not notice the effect of the (initially) small exponentially growing component. But eventually it matters, a lot. We can delay the point where the solution goes bad by controlling the initial velocity more carefully, but this doesn’t buy us much time. If we make ε ten times smaller, we postpone the time when the solution goes bad to 8.41, only a little over a second later.

[Looking at the plot, the solution does not obviously go wrong at t = 7.25. But it does go qualitatively wrong at that point: a solution that should be positive and decreasing becomes either negative or increasing.]

Trying to extend the quality of the solution by making ε smaller is a fool’s errand. Every order of magnitude decrease in ε only prolongs the inevitable by an extra second or so.

This is a somewhat artificial example. The equation and initial conditions were selected to make the sensitive dependence obvious. The sensitive dependence is itself sensitive: small changes to the problem, such as adding a small first derivative term, make it better behaved.

However, sensitive dependence is a practical phenomena. Numerical methods can, for example, pick up an initially small component of an increasing solution while trying to compute a decreasing solution. Sometimes the numerical sensitivity is a reflection of a sensitive physical system. But if the physical system is stable and the numerical solution is not, the problem may not be numerical. The problem may be a bad model. The numerical difficulties may be trying to tell you something, in which case increasing the accuracy of the numerical method may hide a more basic problem.

More differential equation posts