Bitcoin transactions appear to be private because names are not attached to accounts. But that is not sufficient to ensure privacy; if it were, much of my work in data privacy would be unnecessary. It’s quite possible to identify people in data that does not contain any direct identifiers.

I hesitate to use the term pseudonymization because people define it multiple ways, but I’d say Bitcoin addresses provide pseudonymization but not necessarily deidentification.

Privacy and public ledgers are in tension. The Bitcoin ledger is superficially private because it does not contain user information, only addresses [1]. However, transaction details are publicly recorded on the blockchain.

To add some privacy to Bitcoin, addresses are typically used only once. Wallet software generates new addresses for each transaction, and so it’s not trivial to track all the money flowing between two people. But it’s not impossible either. Forensic tools make it possible to identify parties behind blockchain transactions via metadata and correlating information on the blockchain with information available off-chain.

Silent Payments

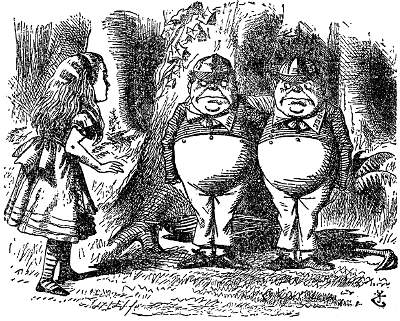

Suppose you want to take donations via Bitcoin. If you put a Bitcoin address on your site, that address has to be permanent, and it’s publicly associated with you. It would be trivial to identify (the addresses of) everyone who sends you a donation.

Silent payments provide a way to work around this problem. Alice could send donations to Bob repeatedly without it being obvious who either party is, and Bob would not have to change his site. To be clear, there would be no way to tell from the addresses that funds are moving between Alice and Bob. The metadata vulnerabilities remain.

Silent payments are not implemented in Bitcoin Core, but there are partial implementations out there. See BIP 352.

The silent payment proposal depends on ECDH (elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman) key exchange, so I’ll do a digression on ECDH before returning to silent payments per se.

ECDH

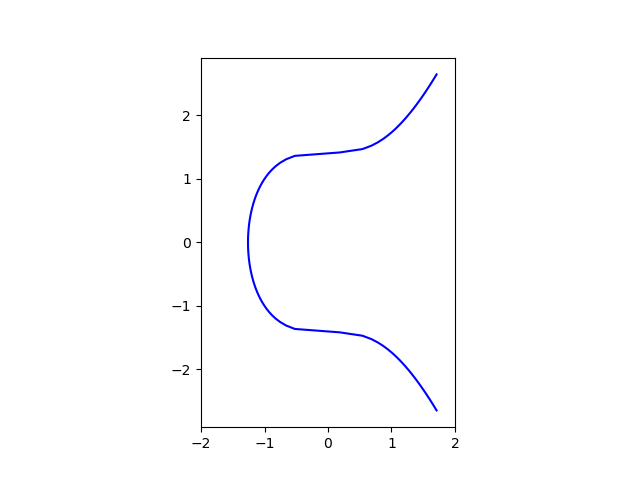

The first thing to know about elliptic curves, as far as cryptography is concerned, is that there is a way to add two points on an elliptic curve and obtain a third point. This turns the curve into an Abelian group.

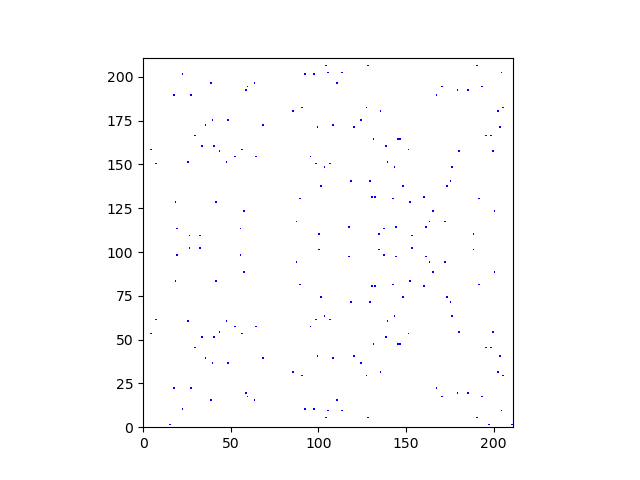

You can bootstrap this addition to create a multiplication operation: given a point g on an elliptic curve and an integer n, ng means add g to itself n times. Multiplication can be implemented efficiently even when n is an enormous number. However, and this is key, multiplication cannot be undone efficiently. Given g and n, you can compute ng quickly, but it’s practically impossible to start with knowledge of ng and g and recover n. To put it another way, multiplication is efficient but division is practically impossible [2].

Suppose Alice and Bob both agree on an elliptic curve and a point g on the curve. This information can be public. ECDH lets Alice and Bob share a secret as follows. Alice generates a large random integer a, her private key, and computes a public key A = ag. Similarly, Bob generates a large random integer b and computes a public key B = bg. They’re shared secret is

aB = bA.

Alice can compute aB because she (alone) knows a and B is public information. Similarly Bob can compute bA. The two points on the curve aB and bA are the same because

aB = abg = bag = bA.

Back to silent payments

ECDH lets Alice and Bob share a secret, a point on a (very large) elliptic curve. This is the heart of silent payments.

In its simplest form, Alice can send Bob funds using the address

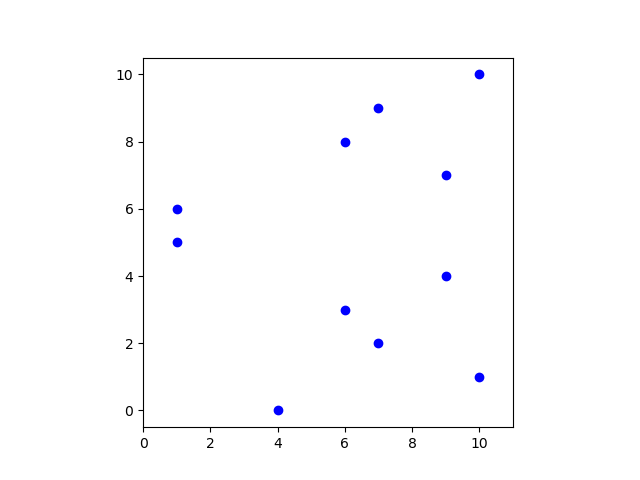

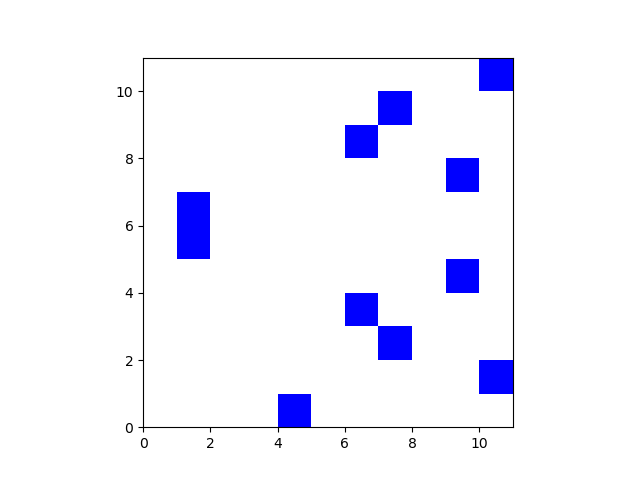

P = B + hash(aB) g.

A slightly more complicated form lets Alice send Bob funds multiple times. The kth time she sends money to Bob she uses the address

P = B + hash(aB || k) g

where || denotes concatenation.

But how do you know k? You have to search the blockchain to determine k, much like the way hierarchical wallets search the blockchain. Is the address corresponding to k = 0 on the blockchain? Then try again with k = 1. Keep doing this until you find the first unused k. Making this process more efficient is one of the things that is being worked on to fully implement silent payments.

Note that Bob needs to make B public, but B is not a Bitcoin address per se; it’s information needed to generate addresses via the process described above. Actual addresses are never reused.

Related posts

[1] Though if you obtain your Bitcoin through an exchange, KYC laws require them to save a lot of private information.

[2] Recovering n from ng is known as the discrete logarithm problem. It would be more logical to call it the discrete division problem, but if you write the group operation on an elliptic curve as multiplication rather than addition, then it’s a discrete logarithm, i.e. trying to solve for an unknown exponent. If and when a large-scale quantum computer exists, the discrete logarithm problem will be practical to solve, but presumably not until then.