The shape of a planet’s orbit around a star is an ellipse. To put it another way, a plot of the position of a planet’s orbit over time forms an ellipse. What about the velocity? Is its plot also an ellipse? Surprisingly, a plot of the velocity forms a circle even if a plot of the position is an ellipse.

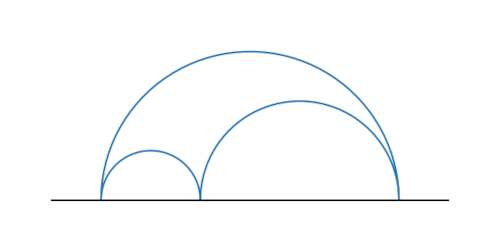

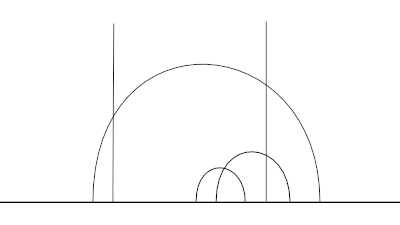

If an object is in a circular orbit, it’s velocity vector traces out a circle too, with the same center. If the object is in an elliptical orbit, it’s velocity vector still traces out a circle, but one with a different center. When the orbit is eccentric, the hodograph, the figure traced out by the velocity vector, is also eccentric, though the two uses of the word “eccentric” are slightly different.

The eccentricity e of an ellipse is the ratio c/a where c is the distance between the two foci and a is the semi-major axis. For a circle, c = 0 and so e = 0. The more elongated an ellipse is, the further apart the foci are relative to the axes and so the greater the eccentricity.

The plot of the orbit is eccentric in the sense that the two foci are distinct because the shape is an ellipse. The hodograph is eccentric in the sense that the circle is not centered at the origin.

The two kinds of eccentricity are related: the displacement of the center of the hodograph from the origin is proportional to the eccentricity of the ellipse.

Imagine the the orbit of a planet with its major axis along the x-axis and the coordinate of its star positive. The hodograph is a circle shifted up by an amount proportional to the eccentricity of the orbit e. The top of the circle corresponds to perihelion, the point closest to the star, and the bottom corresponds to aphelion, the point furthest from the star. For more details, see the post Max and min orbital speed.