A Mersenne prime is a prime number that is one less than a power of 2. These primes are indexed by the corresponding power of two, i.e. Mp = 2p − 1. It turns out p must be prime before 2p − 1 can be prime.

Here are five things I find interesting about Mersenne primes.

1. Record size primes

The largest known prime number is a Mersenne prime, M82,589,993, proved prime in 2018. And ever since M521 was proven prime in 1952, the largest known prime has always been a Mersenne prime (with one exception in 1989). See a history of prime number records.

One reason for the prevalence of Mersenne primes in the record books is that there is a special algorithm for testing whether a number of the form 2p − 1 is prime, the Lucas-Lehmer test.

2. Finiteness

There may only be a finite number of Mersenne primes. Only 51 are known so far. There are conjectures that predict there are an infinite number of Mersenne primes, but these have not been settled.

3. Connection with perfect numbers

Euclid proved that if M is a Mersenne prime, M(M + 1)/2 is a perfect number. Two millennia later, Euler proved that if N is an even perfect number, N must be of the form M(M + 1)/2 where M is a Mersenne prime. (More details here.)

Since we only know of 51 Mersenne primes at the moment, and we don’t know of any odd perfect numbers, there are only 51 known perfect numbers.

4. Connection with random number generation

The Mersenne twister is a popular, high-quality random number generator. The generator is so named because its period is a Mersenne prime, M19,937.

5. History

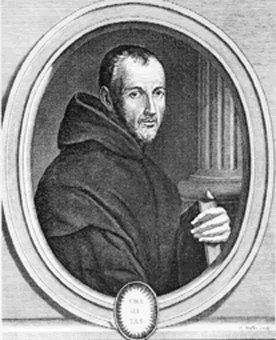

Mersenne primes are named after the French monk Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) who compiled a list of Mersenne primes. Mersenne wasn’t the first to be aware of such primes. As mentioned above, Euclid connected these primes with perfect numbers.

Marin Mersenne is one of my academic ancestors. I studied under Ralph Showalter, who studied under Tsuan Ting, and so forth back to Frans van Schooten Jr., who studied under Marin Mersenne.

What I find fascinating about this is not my particular genealogy, but that adequate records exist to construct such genealogies. The Mathematics Genealogy Project has over 150,000 records, some reaching back to the Middle Ages.