I’ve played saxophone since I was in high school, and I thought I knew how saxophones work, but I learned something new this evening. I was listening to a podcast [1] on musical acoustics and much of it was old hat. Then the host said that a saxophone has two octave holes. Really?! I only thought there was only one.

When you press the octave key on the back of a saxophone with your left thumb, the pitch goes up an octave. Sometimes this causes a key on the neck to open up and sometimes it doesn’t [2]. I knew that much.

I thought that when this key didn’t open, the octaves work like they do on a flute: no mechanical change to the instrument, but a change in the way you play. And to some extent this is right: You can make the pitch go up an octave without using the octave key. However, when the octave key is pressed there is a second hole that opens up when the more visible one on the neck closes.

According to the podcast, the first saxophones had two octave keys to operate with your thumb. You had to choose the correct octave key for the note you’re playing. Modern saxophones work the same as early saxophones except there is only one octave key controlling two octave holes.

* * *

[1] Musical Acoustics from The University of Edinburgh, iTunes U.

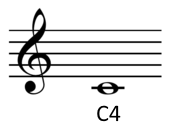

[2] On the notes written middle C up to A flat, the octave key raises the little hole I wasn’t aware of. For higher notes the octave key raises the octave hole on the neck.