The cross ratio of four points A, B, C, D is defined by

where XY denotes the length of the line segment from X to Y.

The idea of a cross ratio goes back at least as far as Pappus of Alexandria (c. 290 – c. 350 AD). Numerous theorems from geometry are stated in terms of the cross ratio. For example, the cross ratio of four points is unchanged under a projective transformation.

Complex numbers

The cross ratio of four (extended [1]) complex numbers is defined by

The absolute value of the complex cross ratio is the cross ratio of the four numbers as points in a plane.

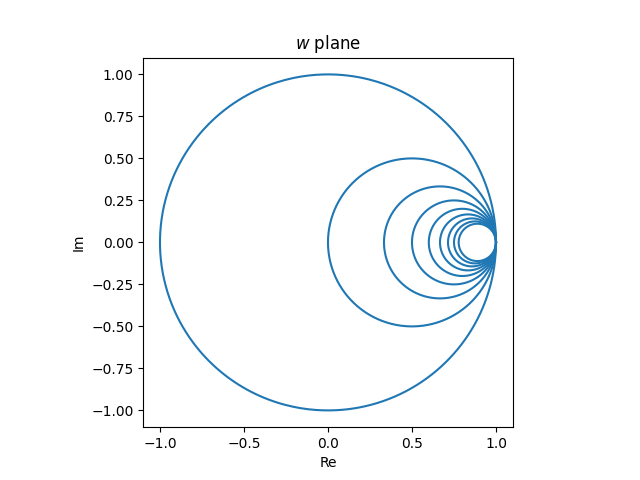

The cross ratio is invariant under Möbius transformations, i.e. if T is any Möbius transformation, then

This is connected to the invariance of the cross ratio in geometry: Möbius transformations are projective transformations on a complex projective line. (More on that here.)

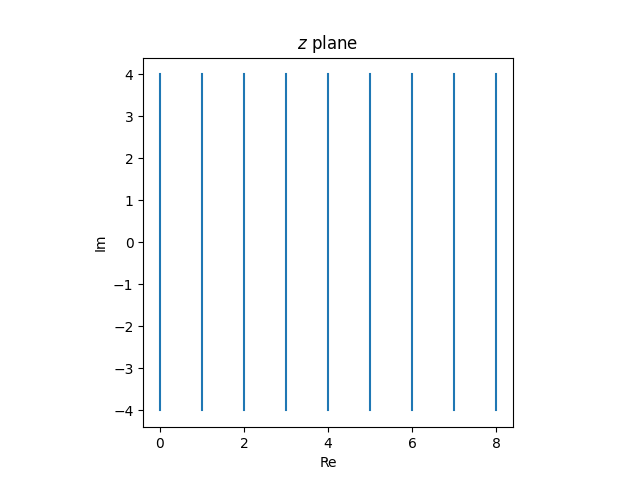

If we fix the first three arguments but leave the last argument variable, then

is the unique Möbius transformation mapping z1, z2, and z3 to ∞, 0, and 1 respectively.

The anharmonic group

Suppose (a, b; c, d) = λ ≠ 1. Then there are 4! = 24 permutations of the arguments and 6 corresponding cross ratios:

Viewed as functions of λ, these six functions form a group, generated by

This group is called the anharmonic group. Four numbers are said to be in harmonic relation if their cross ratio is 1, so the requirement that λ ≠ 1 says that the four numbers are anharmonic.

The six elements of the group can be written as

Hypergeometric transformations

When I was looking at the six possible cross ratios for permutations of the arguments, I thought about where I’d seen them before: the linear transformation formulas for hypergeometric functions. These are, for example, equations 15.3.3 through 15.3.9 in A&S. They relate the hypergeometric function F(a, b; c; z) to similar functions where the argument z is replaced with one of the elements of the anharmonic group.

I’ve written about these transformations before here. For example,

There are deep relationships between hypergeometric functions and projective geometry, so I assume there’s an elegant explanation for the similarity between the transformation formulas and the anharmonic group, though I can’t say right now what it is.

Related posts

[1] For completeness we need to include a point at infinity. If one of the z equals ∞ then the terms involving ∞ are dropped from the definition of the cross ratio.