John Tukey developed his so-called g-and-h distribution to be very flexible, having a wide variety of possible values of skewness and kurtosis. Although the reason for the distribution’s existence is its range of possible skewness and values, calculating the skewness and kurtosis of the distribution is not simple.

Definition

Let φ be the function of one variable and four parameters defined by

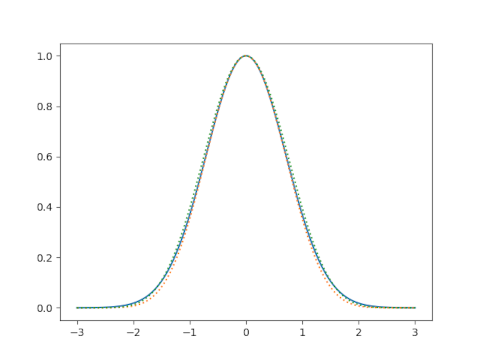

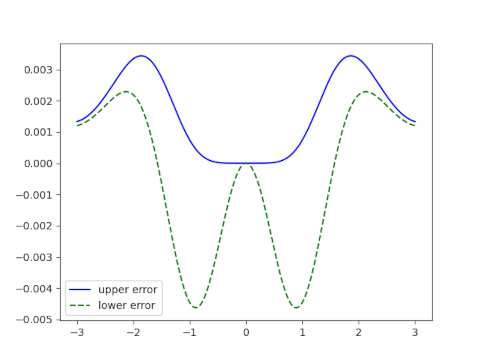

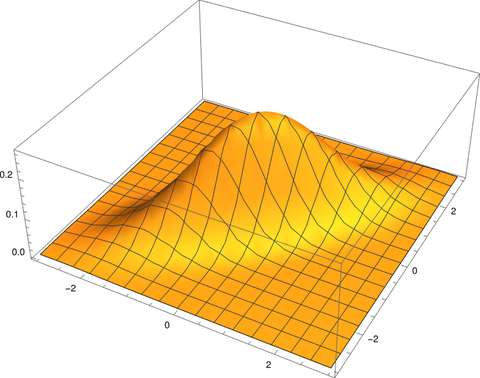

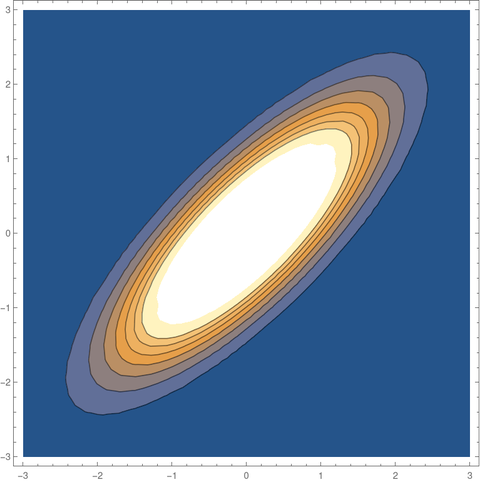

A random variable Y has a g-and-h distribution if it has the same distribution as φ(Z; a, b, g, h) where Z is a standard normal random variable. Said another way, if Y has a g-and-h distribution then the transformation φ−1 makes the data normal.

The a and b parameters are for location and scale. The name of the distribution comes from the parameters g and h that control skewness and kurtosis respectively.

The transformation φ is invertible but φ−1 does not have a closed-form; φ−1 must be computed numerically. It follows that the density function for Y does not have a closed form either.

Special cases

The g distribution is the g-and-h distribution with h = 0. It generalizes the log normal distribution.

The limit of the g-and-h distribution as g does to 0 is the h distribution.

If g and h are both zero we get the normal distribution.

Calculating skewness and kurtosis

The following method of computing the moments of Y comes from [1].

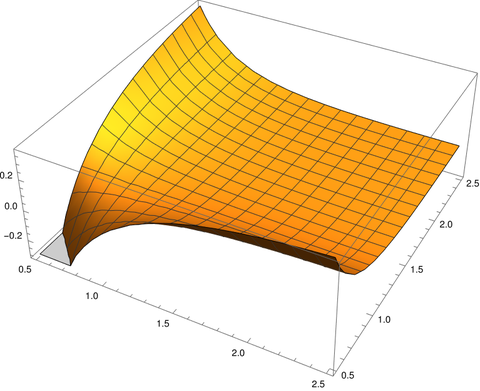

Define f by

Then the raw moments of Y are given by

Skewness is the 3rd centralized moment and kurtosis is the 4th centralized moment. Equations for finding centralized moments from raw moments are given here.

Related posts

[1] James B. McDonald and Patrick Turley. Distributional Characteristics: Just a Few More Moments. The American Statistician, Vol. 65, No. 2 (May 2011), pp. 96–103