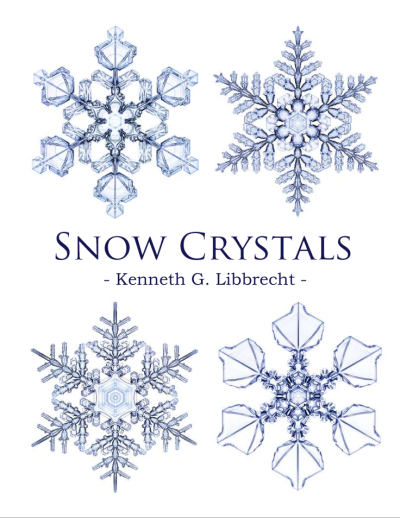

Kenneth G. Libbrecht has posted a 523-page book on snow to arXiv.

Kenneth G. Libbrecht has posted a 523-page book on snow to arXiv.

How many days are in a year? 365.

How many times does the earth rotate on its axis in a year? 366.

If you think a day is the time it takes for earth to rotate once around its axis, you’re approximately right, but off by about four minutes.

What we typically mean by “day” is the time it takes for earth to return to the same position relative to the sun, i.e. the time from one noon to the next. But because the earth is orbiting the sun as well as rotating on its axis, it has to complete a little more than one rotation around its axis to brings the sun back to the same position.

Since there are approximately 360 days in a year, the earth has to rotate about 361 degrees to bring the sun back into the same position. This extra rotation takes 1/360th of a day, or about 4 minutes. (We’ll be more precise below.)

Here’s another way to see that the number of rotations has to be more than the number days in a year. To make the numbers simple, assume there are 360 days in a year. Suppose you’re looking up at the noon sun one day. Next suppose it is exactly 180 days later and the earth had rotated 180 times. Because the earth is on the opposite side of the sun, you would be on the opposite side of the sun too. For it to be noon again 180 days later, the earth would have to have made 180.5 rotations, making 361 rotations in a 360-day year.

Imagine an observer looking straight down at the Earth’s north pole from several light years away. Imagine also an arrow from the center of the Earth to a fixed point on the equator. The time it takes for the observer to see that arrow return to same angle is a sidereal day. The time it takes for that arrow to go from pointing at the sun to pointing at the sun again is a solar day, which is about four minutes longer [1].

If you assume a year has 365.25 (solar) days, but also assume Earth is in a circular orbit around the sun, you’ll calculate a sidereal day to be about 3 minutes and 57 seconds shorter than a solar day. Taking the elliptical shape of Earth’s orbit into account takes about a second off that amount.

[1] Technically this is an apparent solar day, a solar day from the perspective of an observer. The length of an apparent solar day varies through the year, but we won’t go into that here.

A new paper in Science suggests that all human languages carry about the same amount of information per unit time. In languages with fewer possible syllables, people speak faster. In languages with more syllables, people speak slower.

Researchers quantified the information content per syllable in 17 different languages by calculating Shannon entropy. When you multiply the information per syllable by the number of syllables per second, you get around 39 bits per second across a wide variety of languages.

If a language has N possible syllables, and the probability of the ith syllable occurring in speech is pi, then the average information content of a syllable, as measured by Shannon entropy, is

For example, if a language had only eight possible syllables, all equally likely, then each syllable would carry 3 bits of information. And in general, if there were 2n syllables, all equally likely, then the information content per syllable would be n bits. Just like n zeros and ones, hence the term bits.

Of course not all syllables are equally likely to occur, and so it’s not enough to know the number of syllables; you also need to know their relative frequency. For a fixed number of syllables, the more evenly the frequencies are distributed, the more information is carried per syllable.

If ancient languages conveyed information at 39 bits per second, as a variety of modern languages do, one could calculate the entropy of the language’s syllables and divide 39 by the entropy to estimate how many syllables the speakers spoke per second.

According to this overview of the research,

Japanese, which has only 643 syllables, had an information density of about 5 bits per syllable, whereas English, with its 6949 syllables, had a density of just over 7 bits per syllable. Vietnamese, with its complex system of six tones (each of which can further differentiate a syllable), topped the charts at 8 bits per syllable.

One could do the same calculations for Latin, or ancient Greek, or Anglo Saxon that the researches did for Japanese, English, and Vietnamese.

If all 643 syllables of Japanese were equally likely, the language would convey -log2(1/637) = 9.3 bits of information per syllable. The overview says Japanese carries 5 bits per syllable, and so the efficiency of the language is 5/9.3 or about 54%.

If all 6949 syllables of English were equally likely, a syllable would carry 12.7 bits of information. Since English carries around 7 bits of information per syllable, the efficiency is 7/12.7 or about 55%.

Taking a wild guess by extrapolating from only two data points, maybe around 55% efficiency is common. If so, you could estimate the entropy per syllable of a language just from counting syllables.

A story in The New Yorker quotes the following explanation from Arthur Eddington regarding relativity and the speed of light.

Suppose that you are in love with a lady on Neptune and that she returns the sentiment. It will be some consolation for the melancholy separation if you can say to yourself at some—possibly prearranged—moment, “She is thinking of me now.” Unfortunately a difficulty has arisen because we have had to abolish Now … She will have to think of you continuously for eight hours on end in order to circumvent the ambiguity of “Now.”

This reminded me of The Book of Strange New Things. This science fiction novel has several themes, but one is the effect of separation on a relationship. Even if you have faster-than-light communication, how does it effect you to know that your husband or wife is light years away? The communication delay might be no more than was common before the telegraph, but the psychological effect is different.

Related post: Eddington’s constant

What is the closest planet to Earth?

The planet whose orbit is closest to the orbit of Earth is clearly Venus. But what planet is closest? That changes over time. If Venus is between the Earth and the sun, Venus is the closest planet to Earth. But if Mercury is between the Earth and the sun, and Venus is on the opposite side of the sun, then Mercury is the closest planet to Earth.

On average, Mercury is the closest planet to the Earth, closer than Venus! In fact, Mercury is the closest planet to every planet, on average. A new article in Physics Today gives a detailed explanation.

The article gives two explanations, one based on probability, and one based on simulated orbits. The former assumes planets are located at random points along their orbits. The latter models the actual movement of planets over the last 10,000 years. The results are agree to within 1%.

It’s interesting that the two approaches agree. Obviously planet positions are not random. But over time the relative positions of the planets are distributed similarly to if they were random. They’re ergodic.

My first response would be to model this as if the positions were indeed random. But my second thought is that maybe the actual motion of the planets might have resonances that keep the distances from being ergodic. Apparently not, or at least the deviation from being ergodic is small.

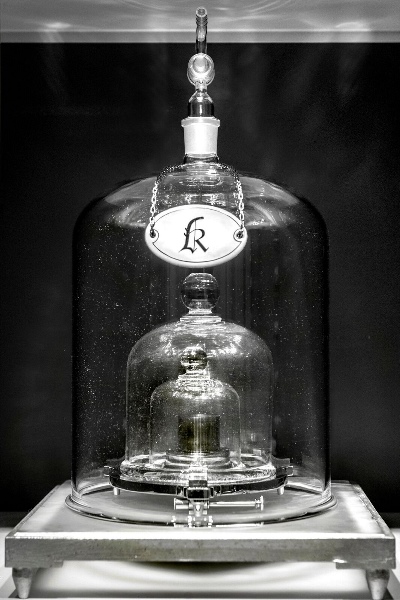

The General Conference on Weights and Measures voted today to redefine the kilogram. The official definition no longer refers to the mass of the International Prototype of the Kilogram (IPK) stored at the BIPM (Bureau International des Poids et Measures) in France. The Coulomb, kelvin, and mole have also been redefined.

The vote took place today, 2018-11-16, and the new definitions will officially begin 2019-05-20.

Until now, Planck’s constant had been measured to be

h = 6.62607015 × 10−34 kg m2 s−1.

Now this is the exact value of Planck’s constant by definition, implicitly defining the kilogram.

The other SI units were already defined in terms of fundamental physical phenomena. The second is defined as

the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the cesium-133 atom

and the statement that the speed of light is

c = 299,792,458 m s−1

went from being a measurement to a definition, much as the measurement of Planck’s constant became a definition [1].

So now the physics of cesium-133 defines the second, the speed of light defines the meter, and Planck’s constant defines the kilogram. There are no more SI units defined by physical objects.

The elementary charge had been measured as

e = 1.602176634 × 10−19 C

and now this equation is exact by definition, defining the coulomb in terms of the elementary charge. And since the ampere is defined as flow of one Coulomb per second, this also changes the definition of the ampere.

The kelvin unit of temperature is now defined in terms of the Boltzmann constant, again reversing the role of measurement and definition. Now the expression

k = 1.380649 × 10−23 kg m2 s−1 K−1

for the Boltzmann constant is exact by definition, defining K.

Avogadro’s number is now exact, defining the mol:

NA = 6.02214076 × 1023 mol−1.

Incidentally, when I first started my Twitter account @UnitFact for units of measure, I used the standard kilogram as the icon.

Then some time later I changed the icon to a Greek mu, the symbol for “micro” used with many units.

The icon for @ScienceTip, however, is Planck’s constant!

It would have been cool if I had anticipated the redefinition of the kilogram and replaced my kilogram icon with the Plank constant icon. (Actually, it’s not Planck’s constant h but the “reduced Planck constant” h-bar equal to h/2π.)

[1] The meter was originally defined in 1791 to be one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole. In 1889, it was redefined to be the distance between two marks on a metal bar stored at BIPM. In 1960 the meter was defined in terms of the spectrum of krypton-86, the first definition that did not depend on an object kept in a vault. In 1983 the definition changed to the one above, making the speed of light exact.

The second was defined in terms of the motion of the earth until 1967 when the definition in terms of cesium-133 was adopted.

The p-norm of a vector is defined to be the pth root of the sum of its pth powers.

Such norms occur frequently in application [1]. Yoshio Koide discovered in 1981 that if you take the masses of the electron, muon, and tau particles, the ratio of the 1 norm to the 1/2 norm is very nearly 2/3. Explicitly,

to at least four decimal places. Since the ratio is tantalizingly close to 2/3, some believe there’s something profound going on here and the value is exactly 2/3, but others believe it’s just a coincidence.

The value of 2/3 is interesting for two reasons. Obviously it’s a small integer ratio. But it’s also exactly the midpoint between the smallest and largest possible value. More on that below.

Is the value 2/3 within the measure error of the constants? We’ll investigate that with a little Python code.

The masses of particles are available in the physical_constants dictionary in scipy.constants. For each constant, the dictionary contains the best estimate of the value, the units, and the uncertainty (standard deviation) in the measurement [2].

from scipy.constants import physical_constants as pc

from scipy.stats import norm

def pnorm(v, p):

return sum(x**p for x in v)**(1/p)

def f(v):

return pnorm(v, 1) / pnorm(v, 0.5)

m_e = pc["electron mass"]

m_m = pc["muon mass"]

m_t = pc["tau mass"]

v0 = [m_e[0], m_m[0], m_t[0]]

print(f(v0))

This says that the ratio of the 1 norm and 1/2 norm is 0.666658, slightly less than 2/3. Could the value be exactly 2/3 within the resolution of the measurements? How could we find out?

The function f above is minimized when its arguments are all equal, and maximized when its arguments are maximally unequal. To see this, note that f(1, 1, 1) = 1/3 and f(1, 0, 0) = 1. You can prove that those are indeed the minimum and maximum values. To see if we can make f larger, we want to increase the largest value, the mass of tau, and decrease the others. If we move each value one standard deviation in the desired direction, we get

v1 = [m_e[0] - m_e[2],

m_m[0] - m_m[2],

m_t[0] + m_t[2]]

print(f(v1))

which returns 0.6666674, just slightly bigger than 2/3. Since the value can be bigger than 2/3, and less than 2/3, the intermediate value theorem says there are values of the constants within one standard deviation of their mean for which we get exactly 2/3.

Now that we’ve shown that it’s possible to get a value above 2/3, how likely is it? We can do a simulation, assuming each measurement is normally distributed.

N = 1000

above = 0

for _ in range(N):

r_e = norm(m_e[0], m_e[2]).rvs()

r_m = norm(m_m[0], m_m[2]).rvs()

r_t = norm(m_t[0], m_t[2]).rvs()

t = f([r_e, r_m, r_t])

if t > 2/3:

above += 1

print(above)

When we I ran this, I got 168 values above 2/3 and the rest below. So based solely on our calculations here, not taking into account any other information that may be important, it’s plausible that Koide’s ratio is exactly 2/3.

***

[1] Strictly speaking, we should take the absolute values of the vector components. Since we’re talking about masses here, I simplified slightly by assuming the components are non-negative.

Also, what I’m calling the p “norm” is only a norm if p is at least 1. Values of p less than 1 do occur in application, even though the functions they define are not norms. I’m pretty sure I’ve blogged about such an application, but I haven’t found the post.

[2] The SciPy library obtained its values for the constants and their uncertainties from the CODATA recommended values, published in 2014.

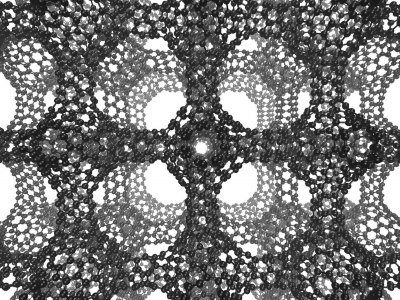

It’s been known for some time that carbon can form structures with positive curvature (fullerenes) and structures with zero curvature (graphene). Recently researches discovered a form of carbon with negative curvature (schwartzites). News story here.

The butterfly effect is the semi-serious claim that a butterfly flapping its wings can cause a tornado half way around the world. It’s a poetic way of saying that some systems show sensitive dependence on initial conditions, that the slightest change now can make an enormous difference later. Often this comes up in the context of nonlinear, chaotic systems but it isn’t limited to that. I give an example here of a linear differential equation whose solutions start out the essentially the same but eventually diverge completely.

Once you think about these things for a while, you start to see nonlinearity and potential butterfly effects everywhere. There are tipping points everywhere waiting to be tipped!

But a butterfly flapping its wings usually has no effect, even in sensitive or chaotic systems. You might even say especially in sensitive or chaotic systems.

Sensitive systems are not always and everywhere sensitive to everything. They are sensitive in particular ways under particular circumstances, and can otherwise be quite resistant to influence. Not only may a system be insensitive to butterflies, it may even be relatively insensitive to raging bulls. The raging bull may have little more long-term effect than a butterfly. This is what I’m calling the other butterfly effect.

In some ways chaotic systems are less sensitive to change than other systems. And this can be a good thing. Resistance to control also means resistance to unwanted tampering. Chaotic or stochastic systems can have a sort of self-healing property. They are more stable than more orderly systems, though in a different way.

The lesson that many people draw from their first exposure to complex systems is that there are high leverage points, if only you can find them and manipulate them. They want to insert a butterfly to at just the right time and place to bring about a desired outcome. Instead, we should humbly evaluate to what extent it is possible to steer complex systems at all. We should evaluate what aspects can be steered and how well they can be steered. The most effective intervention may not come from tweaking the inputs but from changing the structure of the system.

A while back I wrote about how planets are evenly spaced on a log scale. I made a bunch of plots, based on our solar system and the extrasolar systems with the most planets, and said noted that they’re all roughly straight lines. Here’s the plot for our solar system, including dwarf planets, with distance on a logarithmic scale.

This post is a quick follow up to that one. You can quantify how straight the lines are by using linear regression and comparing the actual spacing with the spacing given by the best straight line. Here I’m regressing the log of the distance of each planet from its star on the planet’s ordinal position.

NB: I am only using regression output as a measure of goodness of fit. I am not interpreting anything as a probability.

|-----------+-----------+----------+-----------| | System | Adjusted | Slope | Intercept | | | R-squared | p-value | p-value | |-----------+-----------+----------+-----------| | home | 0.9943 | 1.29e-11 | 2.84e-08 | | kepler90 | 0.9571 | 1.58e-05 | 1.29e-06 | | hd10180 | 0.9655 | 1.41e-06 | 2.03e-07 | | hr8832 | 0.9444 | 1.60e-04 | 5.57e-05 | | trappist1 | 0.9932 | 8.30e-07 | 1.09e-09 | | kepler11 | 0.9530 | 5.38e-04 | 2.00e-05 | | hd40307 | 0.9691 | 2.30e-04 | 1.77e-05 | | kepler20 | 0.9939 | 8.83e-06 | 3.36e-07 | | hd34445 | 0.9679 | 2.50e-04 | 4.64e-04 | |-----------+-----------+----------+-----------|

R² is typically interpreted as how much of the variation in the data is explained by the model. In the table above, the smallest value of R² is 94%.

p-values are commonly, and wrongly, understood to be the probability of a model assumption being incorrect. As I said above, I’m completely avoiding any interpretation of p-values as the probability of anything, only noting that small values are consistent with a good fit.

Journals commonly, and wrongly, are willing to assume that anything with a p-value less than 0.05 is probably true. Some are saying the cutoff should be 0.005. There are problems with using any p-value cutoff, but I don’t want to get into here. I’m only saying that small p-values are typically seen as evidence that a model fits, and the values above are orders of magnitude smaller than what journals consider acceptable evidence.

When I posted my article about planet spacing I got some heated feedback saying that this isn’t exact, that it’s unscientific, etc. I thought that was strange. I never said it was exact, only that it was a rough pattern. And although it’s not exact, it would be hard to find empirical studies of anything with such a good fit. If you held economics or psychology, for example, to the same standards of evidence, there wouldn’t be much left.

This pattern is known as the Titius-Bode law. I stumbled on it by making some plots. I assumed from the beginning that someone else must have done the same exercise and that the pattern had a name, but I didn’t know that name until later.

Someone sent me a paper that analyzes the data on extrasolar planets and Bode’s law, something much more sophisticated than the crude sketch above, but unfortunately I can’t find it this morning. I don’t recall what they did. Maybe they fit a hierarchical model where each system has its own slope and intercept.

One criticism has been that by regressing against planet order, you automatically get a monotone function. That’s true, but you do get a much better fit on a log scale than on a linear scale in any case. You might look at just the relative planet spacings without reference to order.