It’s been said whatever you can validate, you can automate. An AI that produces correct work 90% of the time could be very valuable, provided you have a way to identify the 10% of the cases where it is wrong. Often verifying a solution takes far less computation than finding a solution. Examples here.

Validating AI output can be tricky since the results are plausible by construction, though not always correct.

Consistency checks

One way to validate output is to apply consistency checks. Such checks are necessary, but not sufficient, and often easy to implement. An simple consistency check might be that inputs to a transaction equal outputs. A more sophisticated consistency check might be conservation of energy or something analogous to it.

Certificates

Some problems have certificates, ways of verifying that a calculation is correct that can be evaluated with far less effort than finding the solution that they verify. I’ve written about certificates in the context of optimization, solving equations, and finding prime numbers.

Formal methods

Correctness is more important in some contexts than others. If a recommendation engine makes a bad recommendation once in a while, the cost is a lower probability of conversion in a few instances. If an aircraft collision avoidance system makes an occasional error, the consequences could be catastrophic.

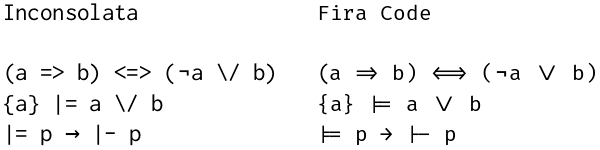

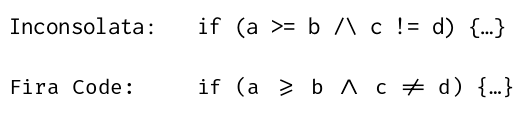

When the cost of errors is extremely high, formal verification may be worthwhile. Formal correctness proofs using something like Lean or Rocq are extremely tedious and expensive to create, and hence not economical. But if an AI can generate a result and a formal proof of correctness, hurrah!

Who watches the watchmen?

But if an AI result can be wrong, why couldn’t a formal proof generated to defend the result also be wrong? As the Roman poet Juvenal asked, Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Who will watch the watchmen?

An AI could indeed generate an incorrect proof, but if it does, the proof assistant will reject it. So the answer to who will watch Claude, Gemini, and ChatGPT is Lean, Rocq, and Isabelle.

Who watches the watchers of the watchmen?

Isn’t it possible that a theorem prover like Rocq could have a bug? Of course it’s possible; there is no absolute certainty under the sun. But hundreds of PhD-years of work have gone into Rocq (formerly Coq) and so bugs in the kernel of that system are very unlikely. The rest of the system is bootstrapped, verified by the kernel.

Even so, an error in the theorem prover does not mean an error in the original result. For an incorrect result to slip through, the AI-generated proof would have to be wrong in a way that happens to exploit an unknown error in the theorem prover. It is far more likely that you’re trying to prove the wrong thing than that the theorem prover let you down.

I mentioned collision avoidance software above. I looked into collision avoidance software when I did some work for Amazon’s drone program. The software that was formally verified was also unrealistic in its assumptions. The software was guaranteed to work correctly, if two objects are flying at precisely constant velocity at precisely the same altitude etc. If everything were operating according to geometrically perfect assumptions, there would be no need for collision avoidance software.