The world’s computer systems kept working on January 1, 2000 thanks to billions of dollars spent on fixing old software. Two wrong conclusions to draw from Y2K are

- The programmers responsible for Y2K bugs were losers.

- That’s all behind us now.

The programmers who wrote the Y2K bugs were highly successful: their software lasted longer than anyone imagined it would. The two-digit dates were only a problem because their software was still in use decades later. (OK, some programmers were still writing Y2K bugs as late as 1999, but I’m thinking about COBOL programmers from the 1970s.)

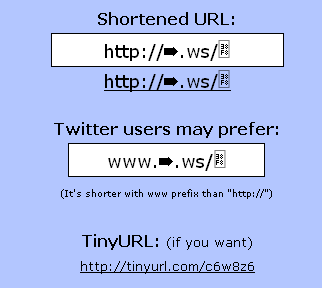

Y2K may be behind us, but we will be facing Y2K-like problems for years to come. Twitter just faced a Y2K-like problem last night, the so called Twitpocalypse. Twitter messages were indexed with a signed 32-bit integer. That means the original software was implicitly designed with a limit of around two billion messages. Like the COBOL programmers mentioned above, Twitter was more successful than anticipated. Twitter fixed the problem without any disruption, except that some third party Twitter clients need to be updated.

We are running out of Internet addresses because these addresses also use 32-bit integers. To make matters worse, an Internet address has an internal structure that greatly reduces the number of possible 32-bit addresses. IPv6 will fix this by using 128-bit addresses.

The US will run out of 10-digit phone numbers at some point, especially since not all 10-digit combinations are possible phone numbers. For example, the first three digits are a geographical area code. One area code can run out of 7-digit numbers while another has numbers left over.

At some point the US will run out of 9-digit social security numbers.

The original Unix systems counted time as the number of seconds since January 1, 1970, stored in a signed 32-bit integer. On January 19, 2038, the number of seconds will exceed the capacity of such an integer and the time will roll over to zero, i.e. it will be January 1, 1970 again. This is more insidious than the Y2K problem because there are many software date representations in common use, including the old Unix method. Some (parts of) software will have problems in 2038 while others will not, depending on the whim of the programmer when picking a way to represent dates.

There will always be Y2K-like problems. Computers are finite. Programmers have to guess at limitations for data. Sometimes these limitations are implicit, and so we can pretend they are not there, but they are. Sometimes programmers guess wrong because their software succeeds beyond their expectations.